Ninetenth-Century Evolutionary Anthropology

“Anthropology, as it was practiced throughout much of the 19th century,” writes Rachel Caspari, “was a single biocultural discipline, with race linking the components.”1 Even though the nineteenth century saw a tremendous intellectual revolution in human biology—the introduction of a formal understanding of evolution—the foundational role of race remained unshaken, even reinforced, by this change.

1 Rachel Caspari, “From Types to Populations: A Century of Race, Physical Anthropology, and the American Anthropological Association,” American Anthropologist 105, no. 1 (2003): 65–76.

This week’s readings center three forms of evolutionary thinking in nineteenth century anthropology, which were tied together in the minds of their advocates: cultural evolution through stages of savagery, barbarism, and civilization; biological evolution of species (and it was presumed, races); and “social Darwinism” to describe the relative success of nations and classes.

Stefanos Gerlounas describes the nineteenth century as a time of three-stage theories of human pre/history, embraced across the century by Comte, Spencer, Tylor, Morgan, Marx, Engels, and Frazer. Lewis Henry Morgan’s Ancient Society2 and Edward Burnett Tylor’s Primitive Culture3 both make the same intellectual move, situating contemporary “savage” cultures as living fossils of a prior “primitive” era in human history, through which “barbarian” and “civilized’ peoples had already passed:

2 Lewis H Morgan, Ancient Society, or Researches in the Lines of Human Progress from Savagery through Barbarism to Civilization (Charles H Kerr; Company, 1877), http://archive.org/details/ancientsociety035004mbp.

3 Edward Burnett Tylor, Primitive culture: Researches into the development of mythology, philosophy, religion, language, art, and custom (Murray, 1920), http://archive.org/details/primitiveculture01tylouoft.

The thesis which I venture to sustain, within limits, is simply this, that the savage state in some measure represents an early condition of mankind, out of which the! higher culture has gradually been developed or evolved, by processes still in regular operation as of old, the result showing that, on the whole, progress has far prevailed over! relapse. (Tylor, p. 32)

The remote ancestors of the Aryan nations presumptively passed through an experience similar to that of existing barbarous and savage tribes. Though the experience of these nations embodies all the information necessary to illustrate the periods of civilization, both ancient and modern. (Morgan)

English professor Patrick Brantlinger is concerned with the rhetoric of extinction attached to Indigenous peoples worldwide by European writers, scientific and otherwise. These discourses were both certain of the impending extinction of savage peoples, and if trouble by it, only troubled from a scientific point of view. Brantlinger argues that these views were generally dismissive:

With a few exceptions—Lewis Henry Morgan and Alfred Russel Wallace are perhaps the main ones—most evolutionists treat primitive races and cultures negatively, not only as doomed by the inexorable laws of nature but also as meriting their pending extinctions. (165)

Dark Vanishings incorporates a wide range of nineteenth century anthropologists including: Thomas Jefferson (Notes on the State of Virginia, 1787); Albert Gallatin (Synopsis of the Indian Tribes of North America, 1836; founder of the American Ethnological Society, 1842) Henry Schoolcraft (The American Indians, Their History, Condition and Prospects); Samuel Morton (Crania Americana, 1839); Lewis Henry Morgan (League of the Iroquois, 1854); Josiah Nott and George Glidden (Types of Mankind, 1854),

We find in Brantlinger a surprising combination of salvage ethnography and celebration of savage demise. While making the case for “keep[ing] some scientific record of that which we destroy”, Pitt-Rivers sees no place for actual native peoples in the future other than in chains: “the savage is morally and mentally an unfit instrument for the spread of civilization, except when, like the higher mammal, he is reduced to slavery; his occupation is gone, and his place is required for an improved race.”

For broader views of American anthropology during this period, consider the earliest chapter in Lee Baker’s From Savage to Negro;4 Glynn Custred in A History of Anthropology As a Holistic Science;5 and many segments of David Hurst Thomas’ Skull Wars.6

4 Lee D Baker, From Savage to Negro: Anthropology and the Construction of Race, 1896-1954 (University of California Press, 1998).

5 Glynn Custred, Anthropology in the Nineteenth Century (Bloomsbury Publishing USA, 2017).

6 David Hurst Thomas, Skull Wars: Kennewick Man, Archaeology, and the Battle for Native American Identity (Basic Books, 2002).

7 Charles Darwin, The Descent of Man (Archives at NCBS, 1901), http://archive.org/details/ncbs.BB-001_0_0_0_1.

Darwin, whose 1859 On the Origin of Species laid out the overall case for biological evolution, delayed direct consideration of the relationship of human to other animals for The Descent of Man, published in 1871.7 While Darwin presumes significant differences among “the races of man” and devotes a chapter to the topic, the text presumes a common human ancestor to all these racial groups and argues forcefully for the species’ overall closeness with primates in particular and animals in general. Nonetheless, racial groups and racial stereotypes are part of the evidentiary landscape used throughout.

Darwin gives priority to organisms’ struggle for survival under conditions of scarcity (the primary form of natural selection in Origin), and secondary consideration to differential rates of reproduction as determined by competition for mates (theorized in Descent). Less considered by Darwin are competitions among groups and species themselves, which would more readily include tendencies towards communication, cooperation, and (a certain form of) altruism.

The first, more competitive form of natural selection became the basis for so-called social Darwinism, framed as “survival of the fittest” and associated with sociologist Herbert Spencer as well as founding eugenicist Francis Galton.

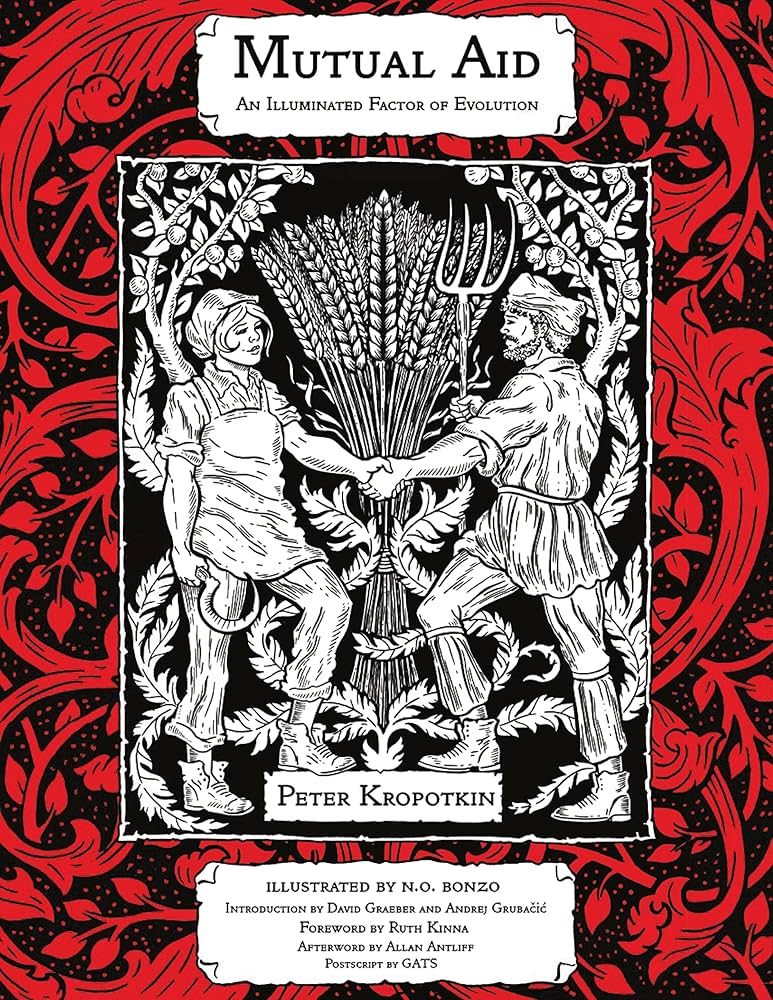

A radically distinct view of natural behavior is presented by Pyotr (“Peter”) Kropotkin in Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution. Kropotkin highlights a wide variety of examples of cooperative behavior among animals (and plants), as well as human at each level of the social evolutionary ladder. While the subject of much skepticism initially, Kropotkin’s overall ideas overlap with Darwin’s, and mutualism within species is taken seriously as a factor in interspecies competition and macroevolution by current biologists.

Stephen Jay Gould (2000:471) even argues that Kropotkin and Darwin’s different emphases stem from their research environments: “In fact, Kropotkin, who was well trained in biology, spoke for a Russian consensus in arguing that density-independent regulation by occasional, but severe, environmental stress will tend to encourage intraspecific cooperation as a mode of natural selection. The harsh environments of the vast Russian steppes and tundras often elicited such a generalized belief; Kropotkin and colleagues had observed well in a local context, but had erred in over generalization. But Darwin and Wallace, schooled in the … tropics, may have made an equally parochial error in advocating such a dominant role for biotic struggle over limited resources in crowded space.”8

8 Stephen Jay Gould, The structure of evolutionary theory (Belknap Press, 2002).

9 Gould, The structure of evolutionary theory.

10 Michael Tomasello, Why We Cooperate, A Boston Review Book (The MIT Press, 2009), https://research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=88bf887e-e045-30b0-a60f-4a9cca13578a.

11 David Sloan Wilson, Does Altruism Exist? : Culture, Genes, and the Welfare of Others, Foundational Questions in Science (Yale University Press, 2014), https://research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=ff9db0f7-14f2-3c57-bb76-19f6ba1dcd7f.

For recent summaries of speciesslevel cooperation and mutualism, see paleontologist and evolutionary biologist Stephen Jay Gould’s chapter on “Species as Individuals in the Hierachical Theory of Selection”9; primatologist Michael Tomasello’s Why We Cooperate;10 and David Sloan Wilson’s Does Altruism Exist?.11

Permalink: https://carwilb.github.io/teaching/history-anthro-w4.html