When did anthropology begin in the Western Hemisphere?

The second week’s readings tries to capture the “dawn” of anthropology in the Western Hemisphere (or perhaps the world engaged by European colonialism). It works not so much by seeking out the first sources chronologically as by capturing the range of different possible voices describing human and cultural others.1

1 Carwil Bjork-James, Indigenous March in Defense of Isiboro Sécure Arrives in La Paz, Challenges Evo Morales Government (Background Briefing), October 16, 2011.

_Brevisima_relación_de_la_destrucción_de_las_Indias.png)

2 Bartolomé de las Casas, Bartolomé de las Casas and the defense of Amerindian rights: a brief history with documents, Atlantic crossings (The University of Alabama Press, 2020).

3 Holger Henke and Fred Reńo, Modern Political Culture in the Caribbean (University of the West Indies Press, 2003).

Chronologically, the readings begin with the 16th century Spanish friar and missionary Bartolomé de las Casas (1484-1566), who wrote about the indigenous peoples of the Caribbean and Central America.2 Las Casas is often credited as one of the first advocates for indigenous rights in the Americas, and his writings provide a critical perspective on the brutal treatment of native populations by European colonizers. Lewis Hanke3 profiles Las Casas as an anthropologist, specifically focusing on “his approach to the study of cultures so alien to his own” who used “the vast amount of material he had patiently gathered on various aspects of Indian life” to “understand the importance of their customs and beliefs within the framework of their own culture.”

Christian Feest profiles4 early European reactions to Aztec and Mesoamerican art brought to Europe in 1521, the moment when the Spanish invasion of the Aztec empire was still ongoing. Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528) is one of the first Europeans to react to Mesoamerican art, and he did so highly positively noting, “And yet I have all days of my life seen nothing that has thus delighted my heart as these things. For I have seen among them wonderful artificial things and have wondered at the subtle ingenia of the people in foreign lands.”

4 Christian F. Feest, A First European Assessment of Indigenous American Art, 1992.

5 Captain Bernardo de Vargas Machuca, A Brief Description of All the Western Indies, ed. Kris Lane, Neil L. Whitehead, Jo Ellen Fair, and Leigh A. Payne (Duke University Press, 2008), 165–212, https://www.degruyterbrill.com/document/doi/10.1515/9780822389064-010/html.

Captain Bernardo de Vargas Machuca5 (1557-1622) took a different view, situating his descriptive work on “the Western Indies” (the Americas, but largely South America) alongside a manual of advice for Spanish soldiers and colonizers and a polemical defense of the conquest against critics like Las Casas.

In American Pentimiento,6 Patricia Seed reflects on Iberian and English descriptions of indigenous peoples in the Americas. She argues that these texts should be read not as straightforward ethnographic accounts but also texts shaped around the need to provide religious and moral justifications for the appropriation of indigenous lands and labor. The optional chapter, “Sustaining Political Identities” summarizes the overall argument of her book, while “Cannibals” details this storytelling in Spanish America.

6 Patricia Seed, American Pentimento: The Invention of Indians and the Pursuit of Riches (University of Minnesota Press, 2001).

7 Roger Williams, A key into the language of America (Bedford, MA : Applewood Books, 1997), http://archive.org/details/bub_gb_wOfpAPRxlVYC.

8 Sarah Vowell, The Wordy Shipmates (Penguin, 2009).

9 Ana González, Roger Williams and the Pequot War, n.d., https://explore.thepublicsradio.org/stories/roger-williams-and-the-pequot-war/.

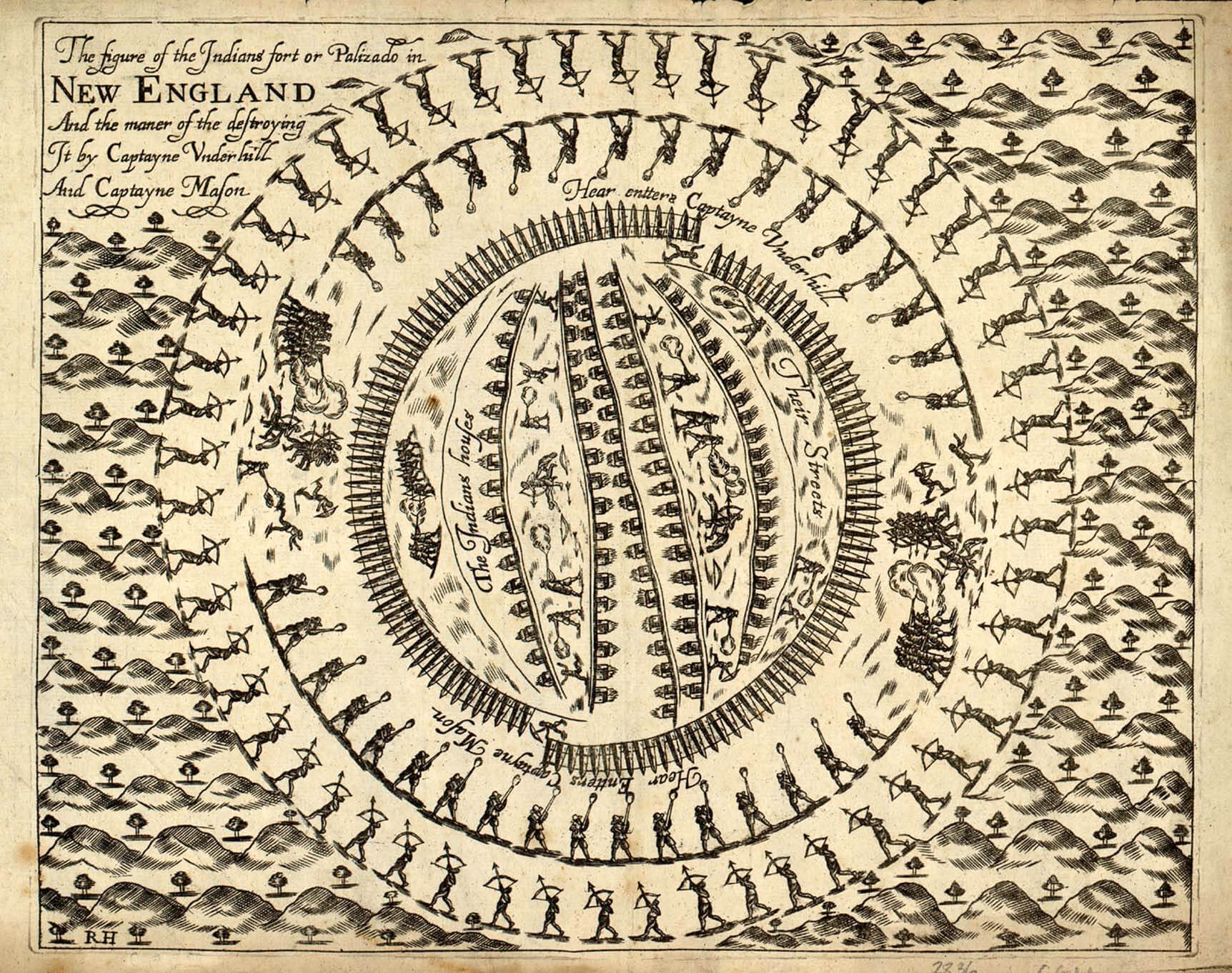

In the English colonization of North America (note that colonization precedes the 1706-07 union forming Great Britain), Roger Williams, the Puritan founder of Rhode Island, is among the first to publish an ethnographic text, A Key into the Language of America (1643).7 The excerpt from Sarah Vowell’s The Wordy Shipmates8 narrates this multivocal text as well as the Pequot War that preceded its publication. This podcast9 focuses on Roger Williams’ direct participation in the Pequot War.

Finally, the first three chapters of Amitav Ghosh’s The Nutmeg’s Curse10 situate the contemporaneous events of the Pequot war and the Dutch conquest of the Banda Islands in 1621-22. Ghosh’s up-close look at early colonial violence speaks to the decisions behind colonial violence as well as the interrelations among different colonial projects and the internal religious wars of Europe. The chapter that follows argues that the colonization of indigenous lands is also interrelated with the de-sacralization of nature in Europe through the scientific revolution.

10 Amitav Ghosh, The nutmeg’s curse: Parables for a planet in crisis (University of Chicago Press, 2021).

Permalink: https://carwilb.github.io/teaching/history-anthro-w2.html