Anthropological grounds for a “revolution in kinship”

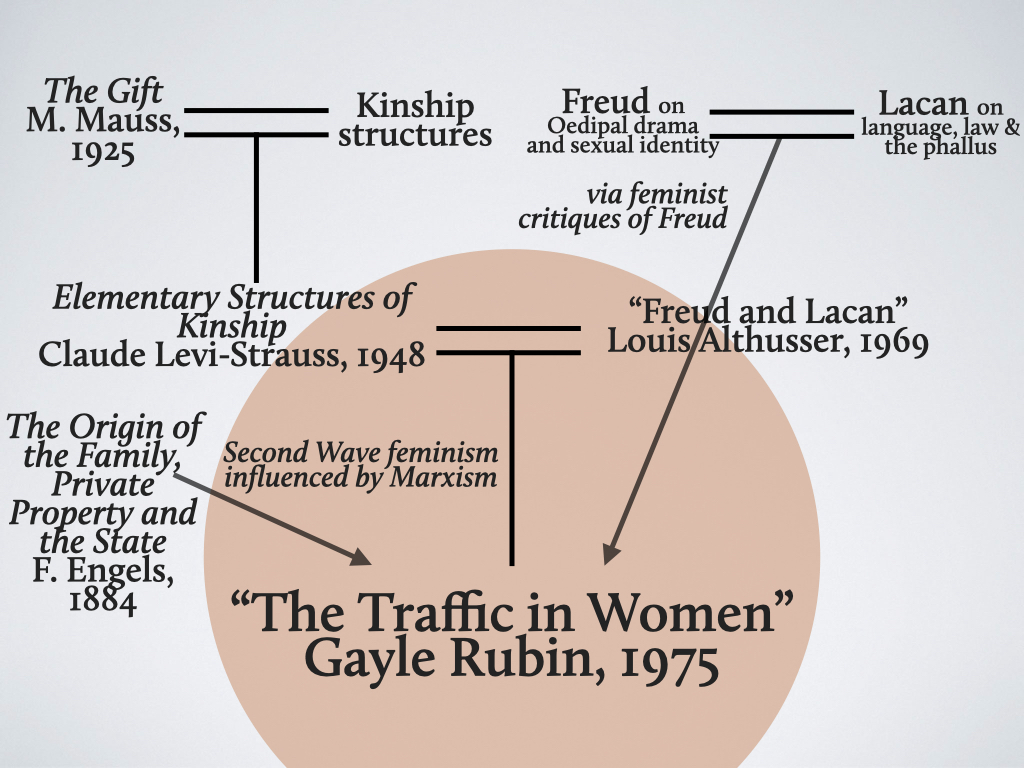

For our final week together, we will be reading Gayle Rubin’s article “The Traffic in Women,” which offers a sophisticated analysis of the interconnection between social taboos, gender identity development, and compulsory heterosexuality, knitting these forces together into a composite “sex/gender system.” Drawing on but greatly extending prior Marxist work on kinship, Rubin proposes that this system functions prior to and alongside the economic sphere investigated by Marx and Engels. Like the economy, the sex/gender system can take multiple shapes over time, with collective action capable of overthrowing one system and instituting another. Rubin suggests (with some ambivalence) the term “patriarchy” to refer to the current dominant mode of the sex/gender system and urges that “Feminism must call for a revolution in kinship” (199).

In Rubin’s telling, gendered behavior, personalities, and marriage behaviors are all integrally related. The social drama of lineages exchanging women, suggested in Mauss’s The Gift and elaborated in Lévi-Strauss’ Elementary Structures of Kinship,1, is at the heart of this story and the (de)formation of personalities into gendered expression is in in service of the exchange. Through gendered socialization, as explored by Mead (though “Traffic” doesn’t mention her directly), de Beauvoir, and (sometimes in faltering way) Freudian psychoanalytic perspectives on gender, women are transformed into give-able social objects.

1 Claude Lévi-Strauss, The Elementary Structures of Kinship, Rev. ed. (Beacon Press, 1969).

The division of labor by sex can therefore be seen as a “taboo”: a taboo against the sameness of men and women, a taboo dividing the sexes into two mutually exclusive categories, a taboo which exacerbates the biological differences between the sexes and thereby creates gender. The division of labor can also be seen as a taboo against sexual arrangements other than those containing at least one man and one woman, thereby enjoining heterosexual marriage.

Following Freud’s theory of infantile sexuality as polymorphous, perverse, and un-differentiated by sex, Rubin narrates the imposition of sex-based personalities as a traumatic imposition (a “straightjacket,” she writes) on both genders. The transformation of this system she envisages would

provide[] us with the opportunity to seize control of the means of sexuality, reproduction, and socialization, and to make conscious decisions to liberate human sexual life from the archic relationsh1pws which deform it. Ultimately, a thorough- going feminist revolution would liberate more than women. It would liberate forms of sexual expression, and it would liberate human personality from the straightjacket of gender.

There are solid Wikipedia articles on Gayle Rubin herself and on “The Traffic in Women.” Finally, Rubin offers an especially rich reflection on her writing in a 1994 interview with Judith Butler.2

2 Gayle Rubin and Judith Butler, “Interview: Sexual Traffic,” Differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies 6, nos. 2-3 (1994): 62–99.

Theoretical Influences

Rubin draws on a truly remarkable number of theoretical referents, making “The Traffic in Women” into something of a theoretical crossroads. On the one hand, we have been tracing our way along many of these pathways, making us especially well-informed readers of this piece. On the other hand, there will be other threads that are unfamiliar. Don’t worry about just trusting Rubin’s account of these sources.

Nevertheless, if you want to follow some of these pathways yourself, here are some resources.

The Oedipus Complex

A just-enough video introduction to the Oedipus Complex from the Freud Museum London. The core takeaways are these: 1. While the existence of an Oedipal drama within every household may seem far-fetched, it is primarily a language for talking about permitted and forbidden attachment to parental figures; 2. Freudian theory posits that learning the social limits on one’s sexuality happens simultaneously with learning one’s gender identity; and 3. learning proper identity is a complex process that runs differently in each individual.

A more complete walk-through of Freud’s theory of psychosexual development is in Lecture XXI of Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis.3 Here is how #3 above is framed there:

3 Sigmund Freud, Introductory lectures on psychoanalysis (Norton, 1977).

From this time onwards, the human individual has to devote himself to the great task of detaching himself from his parents, and not until that task is achieved can he cease to be a child and become a member of the social community. … These tasks are set to everyone; and it is remarkable how seldom they are dealt with in an ideal manner - that is, in one which is correct both psychologically and socially.4

4 Freud, Introductory lectures on psychoanalysis, 380–81.

Freud, Lévi-Strauss, and Lacan on the Incest Prohibition and the Law

In Totem and Taboo,5 Freud describes the incest taboo as a historical event that helped to define civilization itself. In this book we find Freud engaging in armchair anthroplogy, and a version in which “savagery”, childhood, and neuroses all serve as analogues for one another. The individual Oedipal drama has a collective counterpart: the desire of the primal male horde to murder the tribal leader who monopolized women in the hypothetical community. The prohibition this murder is accomplished through instituting both law and religion. Here is a brief narration of that drama.

5 Sigmund Freud, Totem and Taboo (Moffat, Yard, 1918), http://archive.org/details/freud-1918-totem-and-taboo.

Lévi-Strauss takes up this Freudian story in Elementary Structures, but is emphatic that it is ahistorical. Instead the incest taboo itself becomes the necessary equivalent of any (and not just “civilized”) society. Lévi-Strauss’ enngament with Freud comes in Chapter XXIX.

Meanwhile Lacan expands on the theme of the Law having its origin in the moment of Oedipal prohibition, or equivalently in the moment of encountering sex-linked expectations on one’s behavior: “The primordial Law is therefore that which in regulating marriage ties superimposes the kingdom of culture on that of a nature abandoned to the law of mating.”6 Much of what is often attributed to Lacan is present in the original writings by Freud and Daniel Hourigan does the deep dive on these themes.7

6 Jacques Lacan, Alan Sheridan, and Malcolm Bowie, The Function and Field of Speech and Language in Psychoanalysis (Routledge, 2001), 73.

7 Daniel Hourigan, “Law on the Other Side of Oedipus: Freud and Lacan on Law and Self-Formation,” Law, Culture and the Humanities, April 24, 2024, 17438721241234195, https://doi.org/10.1177/17438721241234195.

Structures of Kinship

This section is repeated from Week 12.

8 Lévi-Strauss, The Elementary Structures of Kinship.

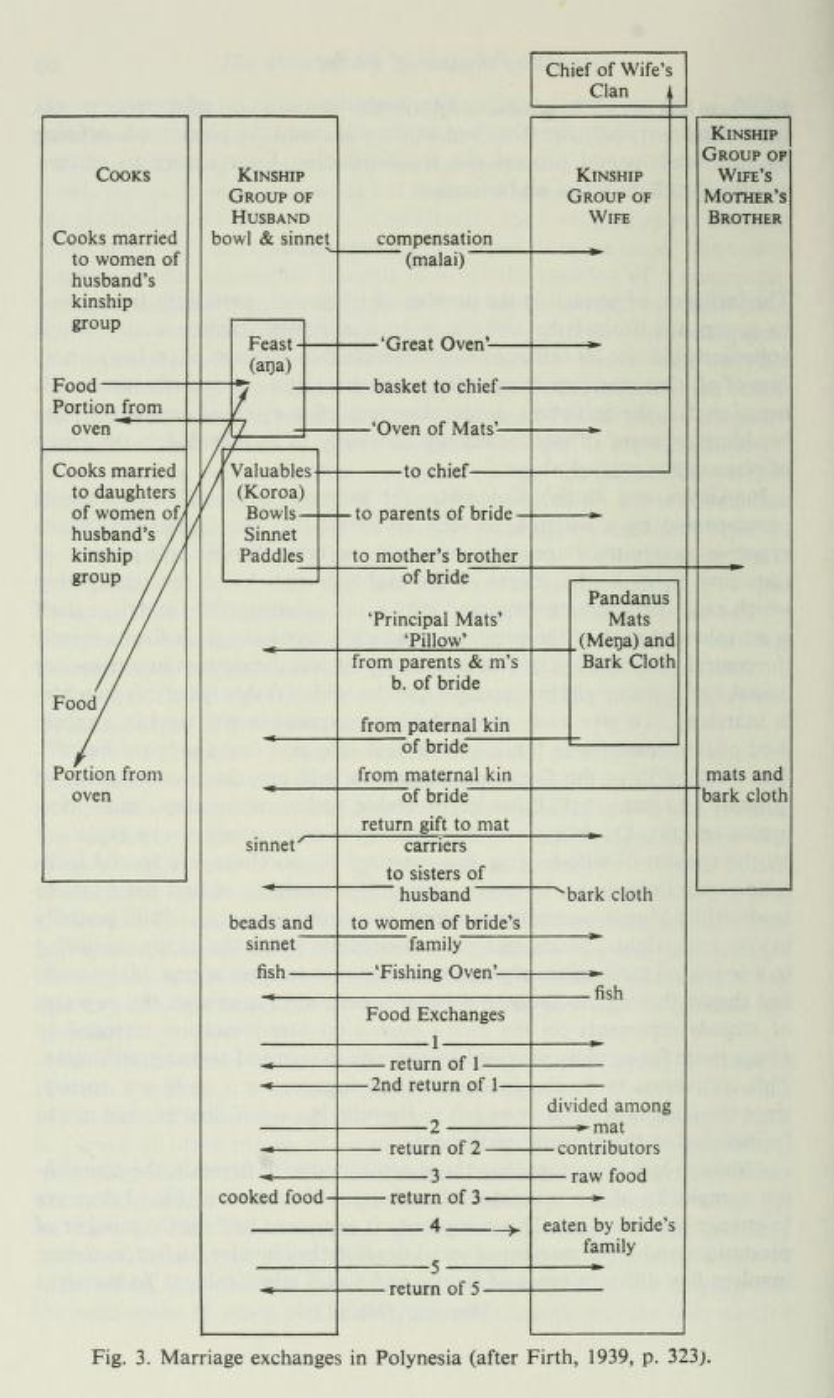

In Elementary Structures of Kinship,8 Claude Lévi-Strauss proposes a structuralist explanation for the circulation of spouses mentioned in Mauss’s The Gift. The core insight of the book is to unite the near-universal taboo on incest (in some form) with the complex kinship structures that anthropologists had been mapping since at least Lewis Henry Morgan. (Like Douglas, he rejects the functionalist explanation that incest taboos prevent interbreeding.)

Lévi-Strauss argues that by separating marriageable from un-marriageable individuals, kinship systems generate the necessary boundaries for lineages that are the collective social actors which exchange spouses—glossed in his account, as in Mauss’s brief phrase, exclusively as women.

Gayle Rubin will build upon Elementary Structures of Kinship in her pivotal essay “The Traffic in Women,”9 which theorizes kinship and gender systems as integrated whole, subject to historical change, and as systems of power.

9 Gayle Rubin, The Traffic in Women: Towards a Political Economy of Sex, ed. Rayna Reiterc (Monthly Review Press, 1975).

And if men have been sexual subjects—exchangers—and women sexual semi-objects—gifts—for much of human history, then a great many customs, clichés, and personality traits seem to make a great deal of sense (among others, the curious custom by which a father gives away a bride).

This essay proves foundational to Gender Studies. Both Rubin and Judith Butler will bring vast inquiries into gender, the body, and sexuality into dialogue with Lévi-Strauss’ account.