Nineteenth-century North American ethnography by Mooney and Morgan

The research monographs that this week’s readings shadow are Lewis Henry Morgan’s League of the Ho-dé-no-sau-nee, or Iroquois and James Mooney’s The ghost-dance religion and the Sioux outbreak of 1890. For a recommended sample of Mooney’s work, see Chapter 2: “The Doctrine of the Ghost Dance”.

Historical context of the Ghost Dance

The colonization of the Great Plains through the Indian Wars is the context for the spread of the Ghost Dance religion. The Fort Laramie Treaties had recognized native sovereignty over the Great Plains in 1851, but volunteer and Federal Army troops began a new round of Indian Wars in the 1860s. Genocidal massacres, military internment, and the undermining of the Indian food supply followed in the succeeding decades. Killing buffalo as a tactic of counterinsurgency was pursued with abandon, as praised by General Philip Sheridan in 1875:

These men [the buffalo hunters] have done … more to settle the vexed Indian question than the entire regular army has done in the last 30 years. They are destroying the Indians’ commissary. … Send them powder and lead if you will, but for the sake of lasting peace let them kill, skin, and sell until the buffalo are exterminated.1

1 Quoted in Winona LaDuke, All Our Relations: Native Struggles for Land and Life (South End Press, 1999), 141.

These measures constituted successive attacks on the physical and cultural mechanisms of survival of the Indians. And consciously so, as can be seen from the opinion of General William Tecumseh Sherman as early as 1867, “We must act with vindictive earnestness against the [Lakota], even to their extermination, men, women and children.”.2 The impact was devastating, as Dee Brown describes for the summer of 1874,

2 Ward Churchill, A Little Matter of Genocide: Holocaust and Denial in the Americas, 1492 to the Present (City Lights, 1997), 240.

If such a season [of drought] had come upon this land a few years earlier, a thunder of a million buffalo hooves would have shaken the prairie in frantic stampedes for water. But now the herds were gone, replaced by an endless desolation of bones and skulls and rotting hooves. … Bands of Comanches, Kiowas, Cheyennes, and Arapahos roamed restlessly, finding a few small herds, but many had to return to their reservations to keep from starving.3

3 Dee Brown, Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee: An Indian History of the American West, Thirtieth Anniversary ed. (H. Holt, 2001), 268.

Those who chose the path of a negotiated surrender to reservations, as did those led by Sitting Bull in 1881, saw agreements for rations and safety undermined. Just two years after that agreement, Sitting Bull—noting “our rations have been reduced to almost nothing” and “many of our people have starved to death”—made a plea for material equality as a corollary of negotiation:

You white men advise us to follow your ways, and therefore I talk as I do. When you have a piece of land, and anyone trespasses on it, you catch them, and keep them until you get damages, and I am doing the same thing now…. I see my people starving, and I want the Great Father to make an increase in the amount of food that is allowed us now, so that they may be able to live. We want cattle to butcher—I want to kill 300 head of cattle at a time. That is the way you live and we want to live the same way.4

4 LaDuke, All Our Relations, 97.

Notwithstanding their pleas, more than one-third of the Lakota would die of starvation and disease between 1877 and 1890.5 The self-sufficiency of the Indians of the Great Plains was undermined on the terrain of physical survival, through the imposition of facts on the ground.

5 LaDuke, All Our Relations, 97.

Here is my recorded lecture segment on the historical context of the Ghost Dance:

{{<video https://youtu.be/dCuBskJzLo4 >}}

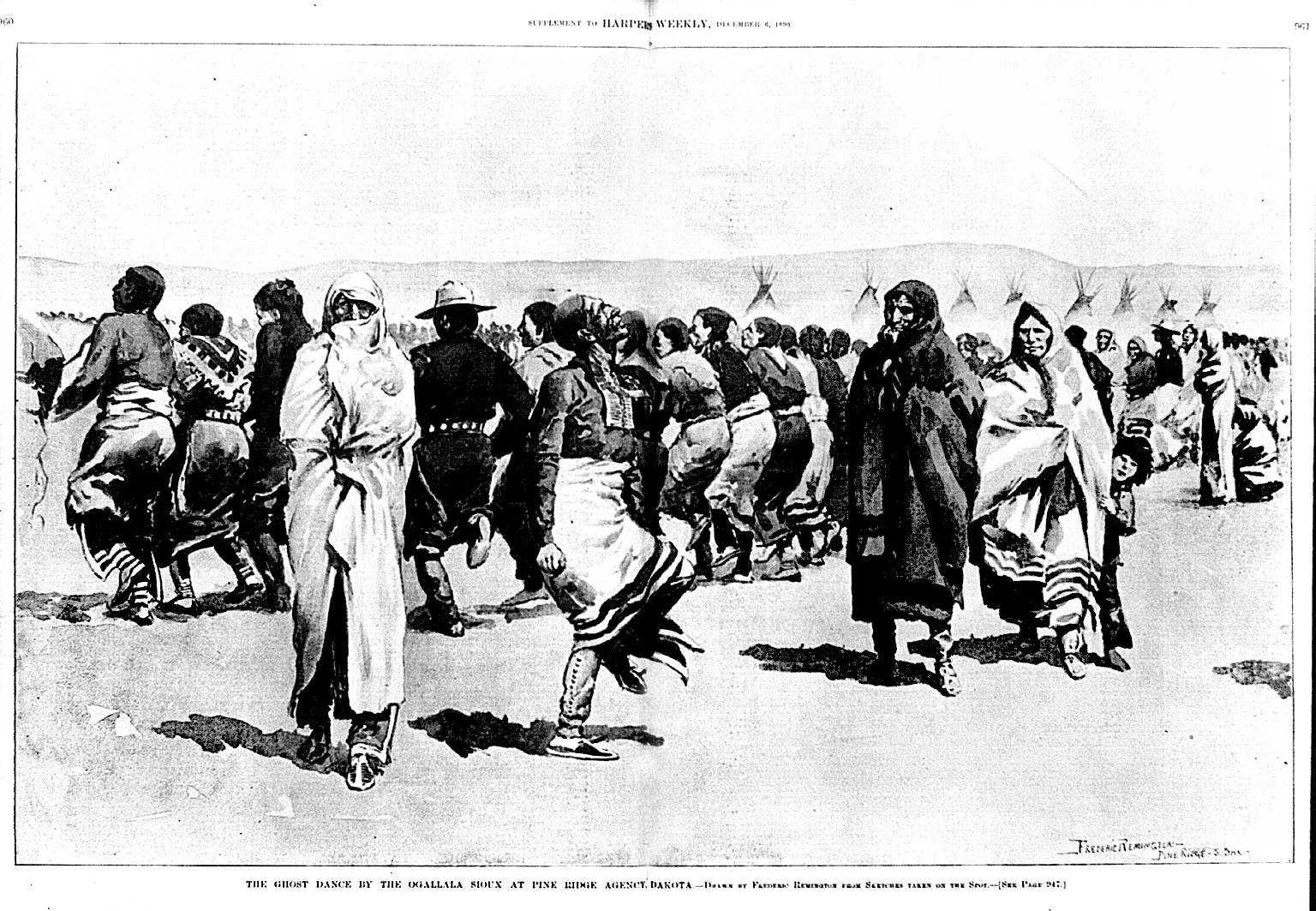

Anthropologist Ella Deloria featured an eyewitness account of the Ghost Dance from an elder who a child during the peak of the religion.