-

Lethal repression often fails, "leading to power shifts by increasing the internal solidarity of the resistance campaign, creating dissent and conflicts among [regime] supporters, [and] increasing external support for the resistance campaign" (Chenoweth & Stephan 2011).

-

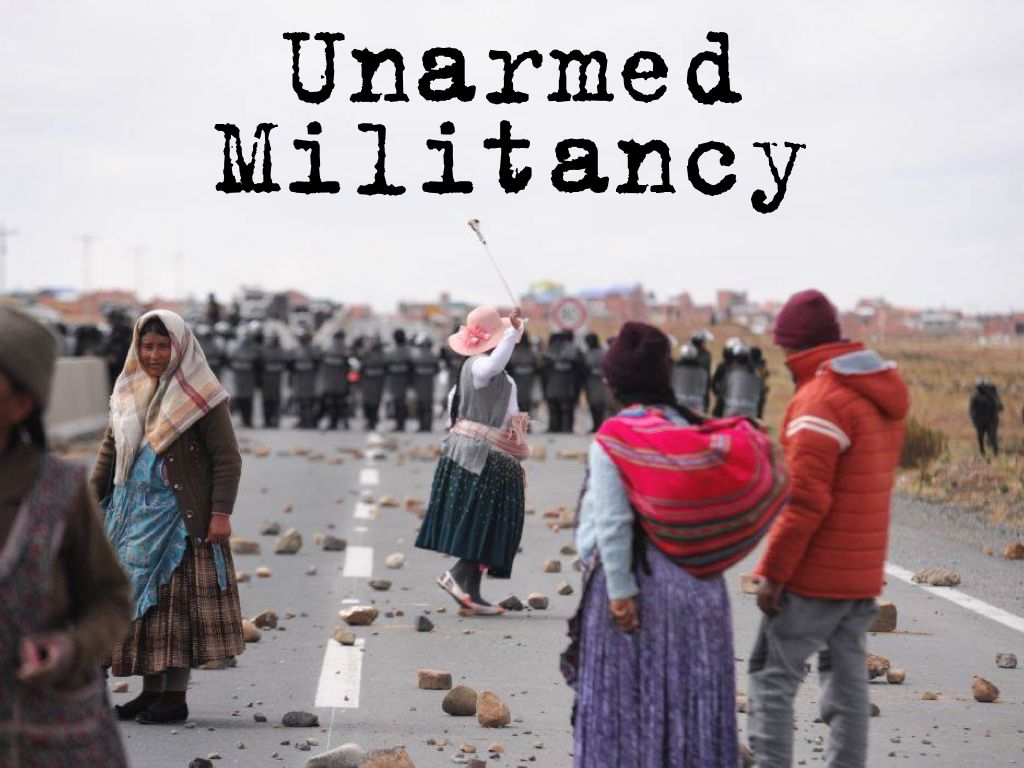

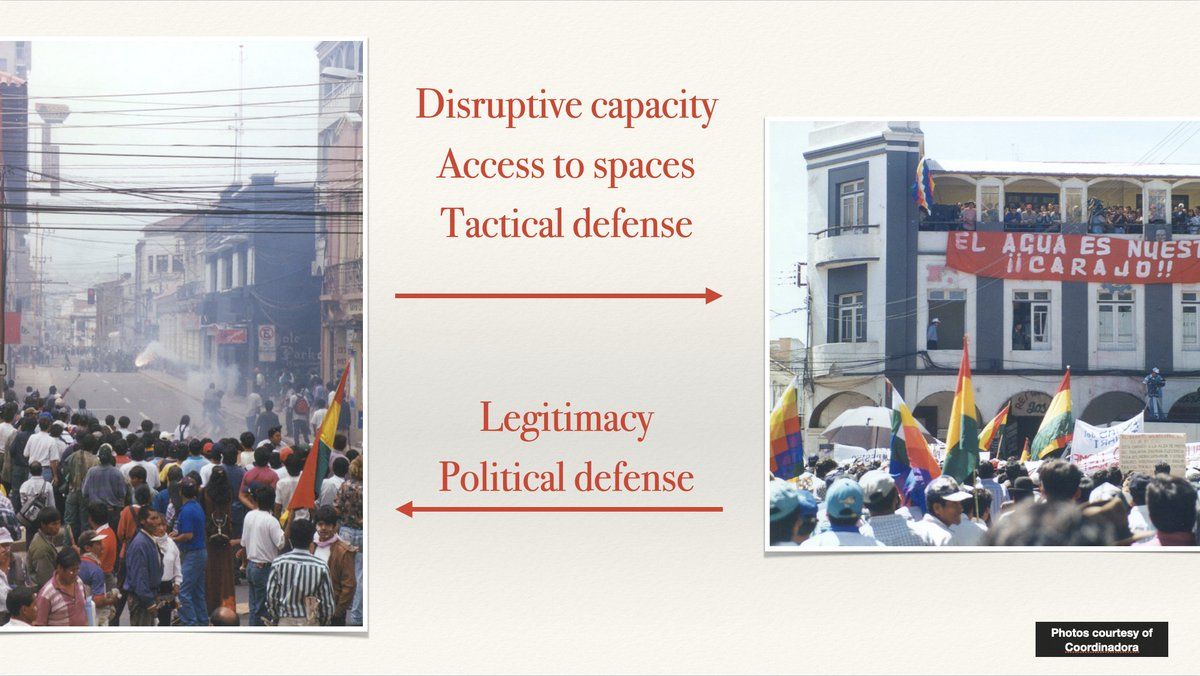

Unarmed militants refuse to yield in confrontations with state forces; they fight back in uneven contests in order to hold physical space, obstruct the flows of daily life, and impose social costs.

-

Unarmed militants often maintain cooperative, even immersive, relationships with larger mass movements, particularly in mass movements of the Global South. The relationship can be mutually beneficial. woborders.blog/published-elsewhere/unarmed-militancy/

-

However, theorists of backfire (Martin, Sharp, Lakey, Chenoweth & Stephan) are generally skeptical of any fighting back, something that runs counter to the tradition of nonviolence from which it, and the equivalent "political jiu-jitsu" emerged.

-

Chenoweth and Stephan argue that both the likelihood and the strength of backfire are amplified when a movement maintains nonviolent discipline and clear contrast between their nonviolent means and the violence used by their state opponents.

-

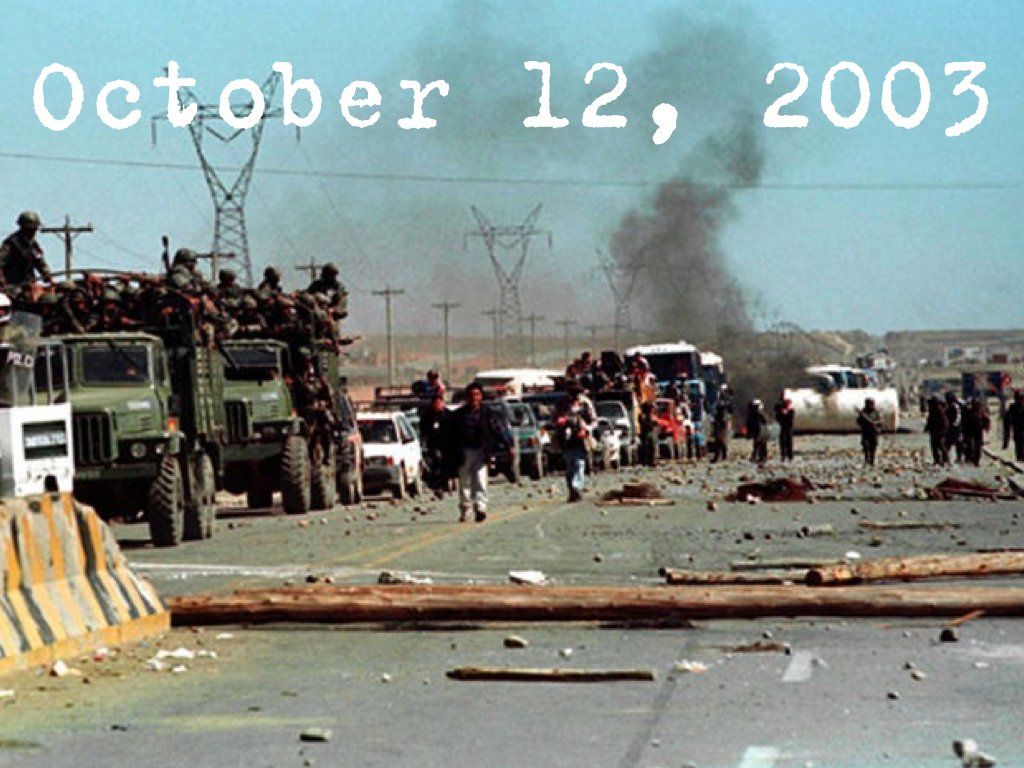

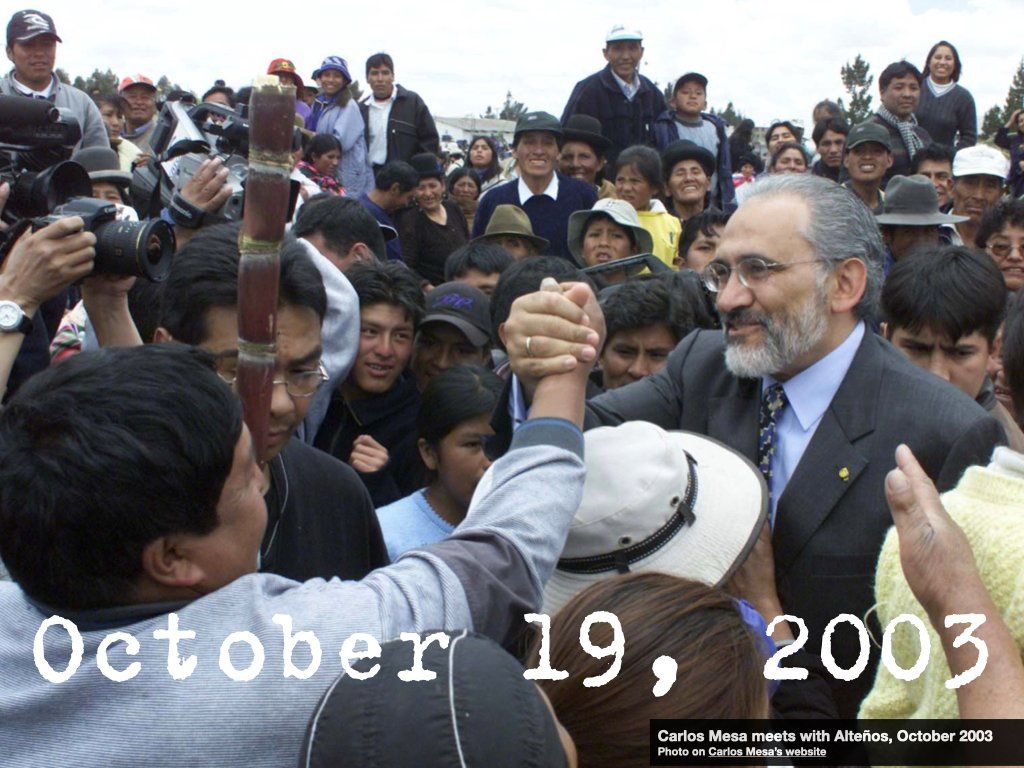

Chenoweth's advice: "‘neither fighting back with their own counterviolence or … retreating in disarray." But Bolivian movements responded differently, fighting to hold space, and sometimes causing fatalities among security forces. What happened then? x.com/CarwilBJ/status/1783876854421549205