-

In ten months of 2003, Bolivian security forces killed a total of 101 Bolivians during protest campaigns. Yet, ended up conceding the protester's demands in every major conflict. When and how does deadly repression fail? I studied 48 episodes of deadly conflict to find out. 🧵

-

A small-scale example: July 2003 protests in Santa Rosa del Sara demanded jobs, roads, and settlement of a land conflict. They blockaded the highway and shut off a gas pipeline. 350 police and soldiers intervened to quell the protests.

-

The troops were initially able to retake control of the pipeline valve, but were soon confronted by 1,500 of the town’s 4,000 residents. During a three-hour clash, eight civilians and seven troops were wounded; and protester Luis Zelaya Márquez was shot dead.

-

Instead of instilling fear, Zelaya’s death only served to anger the crowd, who proceeded to retake the pipeline valve. Despite their advantage in weapons, security forces backed off.

-

Politicians and the media disavowed the military-police intervention at Santa Rosa del Sara as a failure and even a moral atrocity. The government met protest demands, and named the highway after Zelaya Márquez.

-

Similarly, during the 2003 "Gas War," Bolivian security forces killed at least 59 people in an unsuccessful attempt to stop protests. In the end, the president resigned instead.

-

This is backfire, Brian Martin's (@brianinthegong) term for situations where violent repression generates sympathy for those it attacks, inspires greater mobilization, alienates elites and external supporters.

-

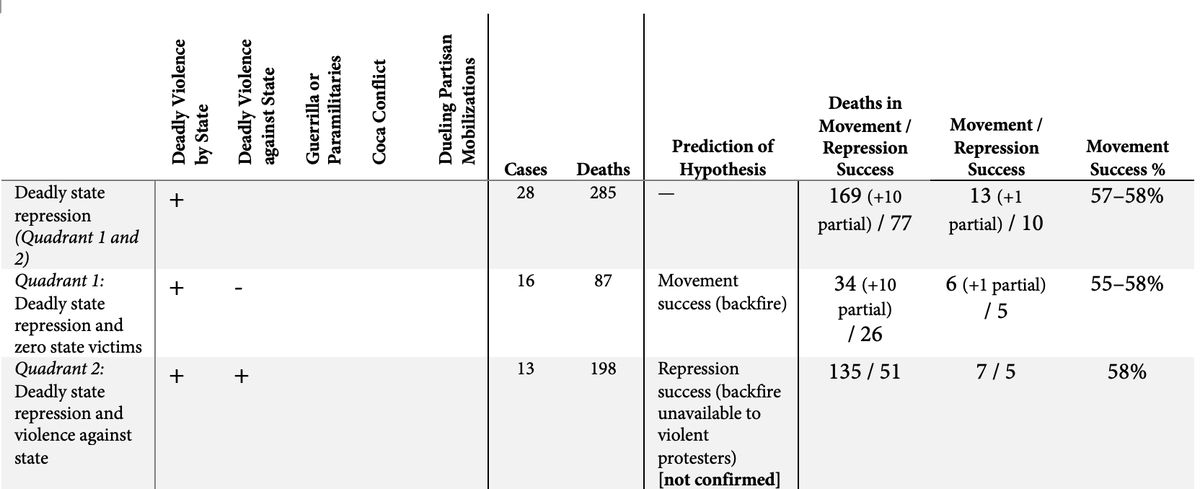

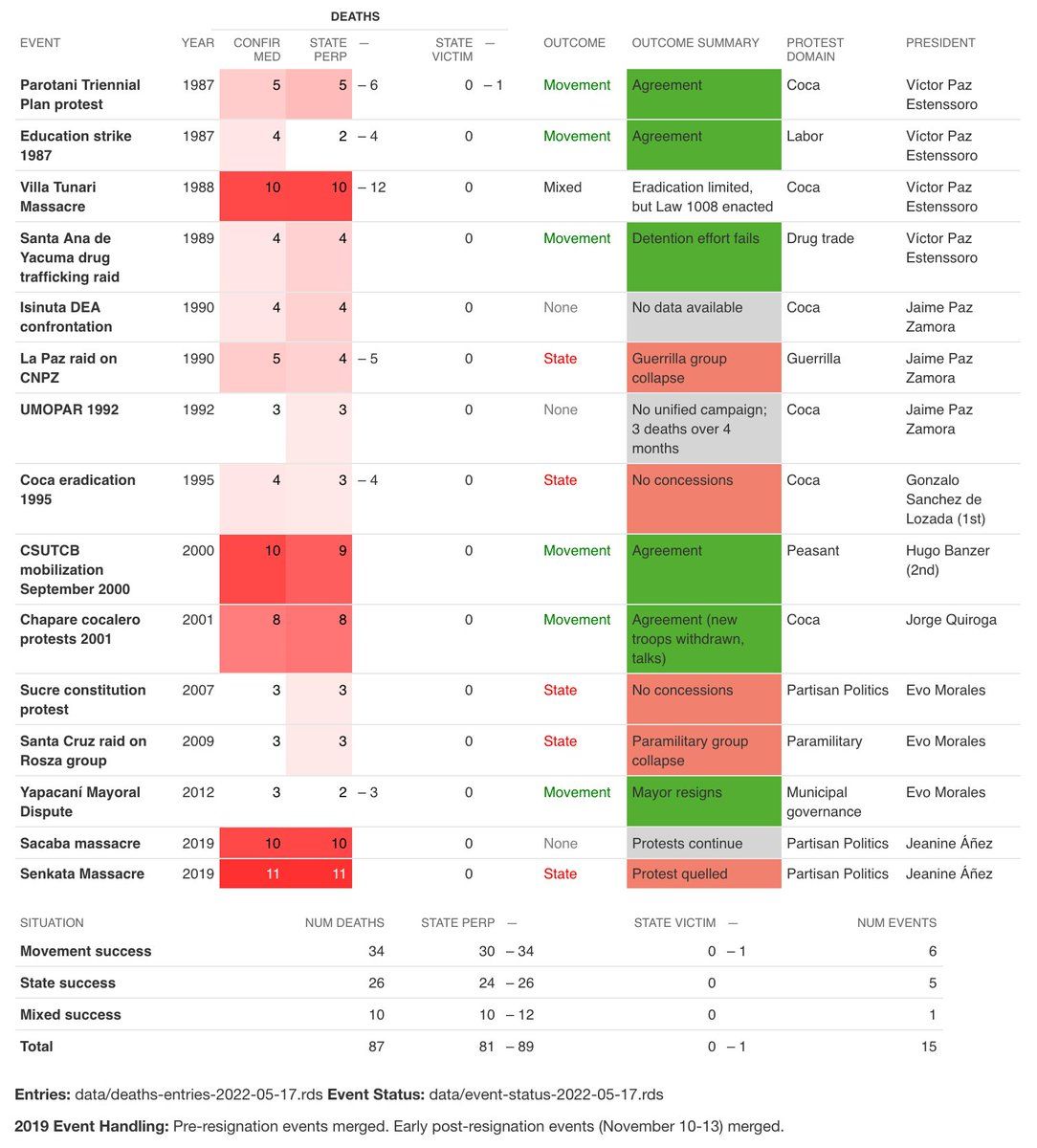

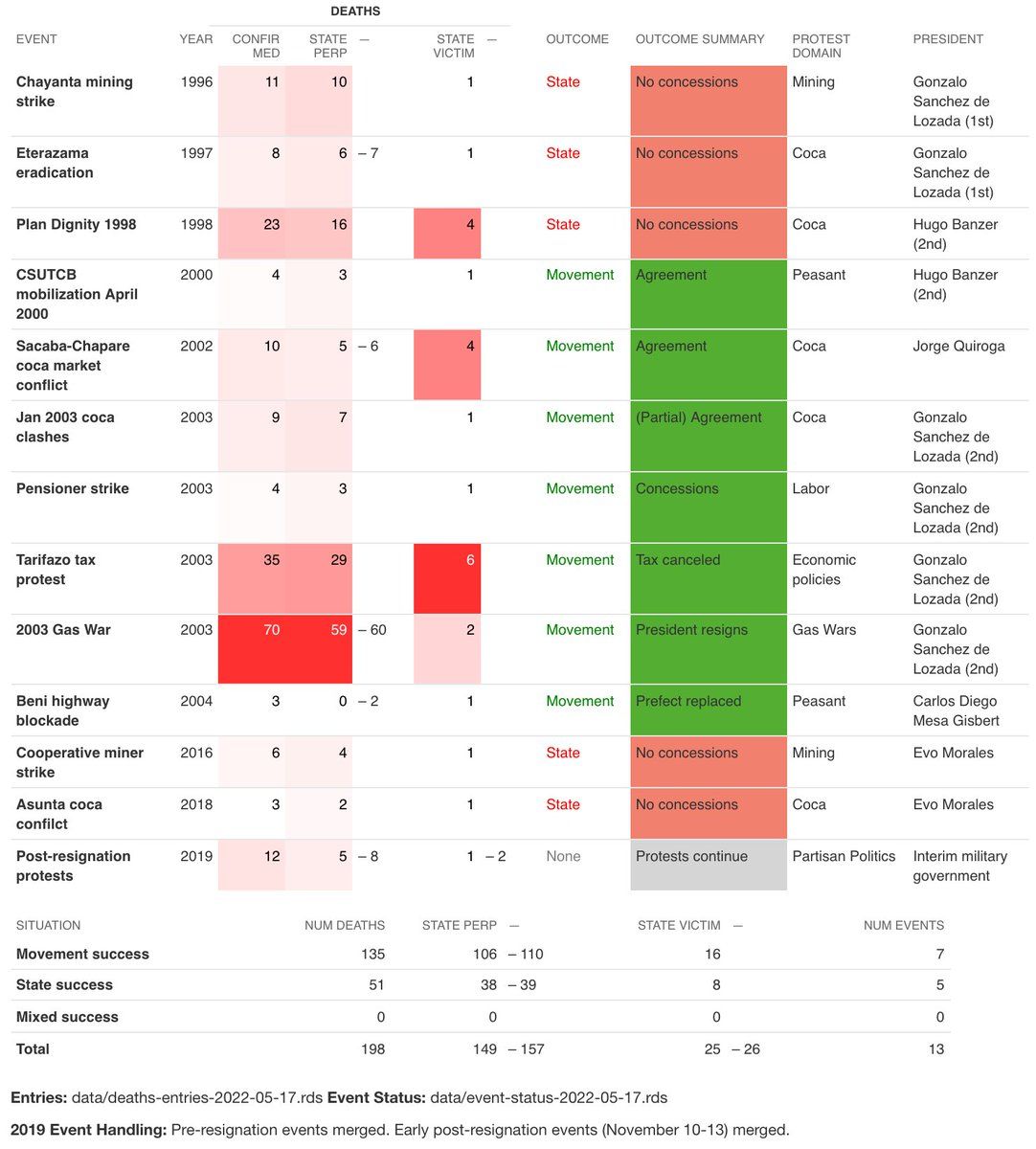

More often than not, when the Bolivian government cracked down over recent decades, their repression backfired. There are 13 cases of movement victories after 3 or more deaths. And just 10 of state success. But…

-

While backfire is the modal outcome of repression in Bolivia, it is not happening when predicted by scholars of backfire, nonviolence, and civil resistance.

-

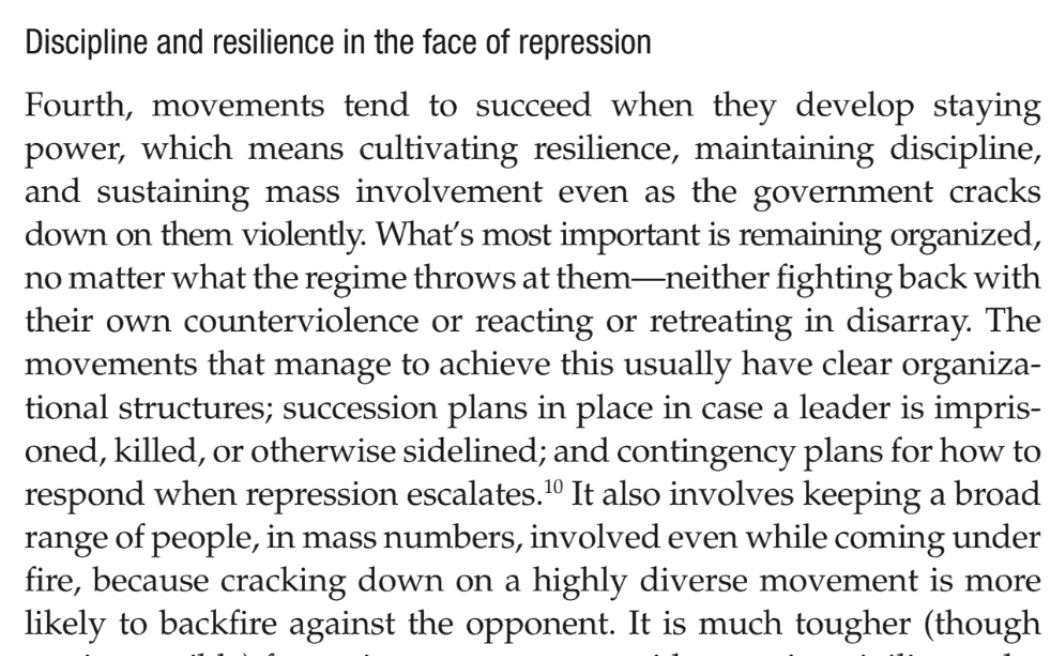

Here's Erica Chenoweth (@EricaChenoweth) summarizing the turning point brought on by repression: "cultivating resilience, maintaining discipline, and sustaining mass involvement even as the government cracks down on them."

-

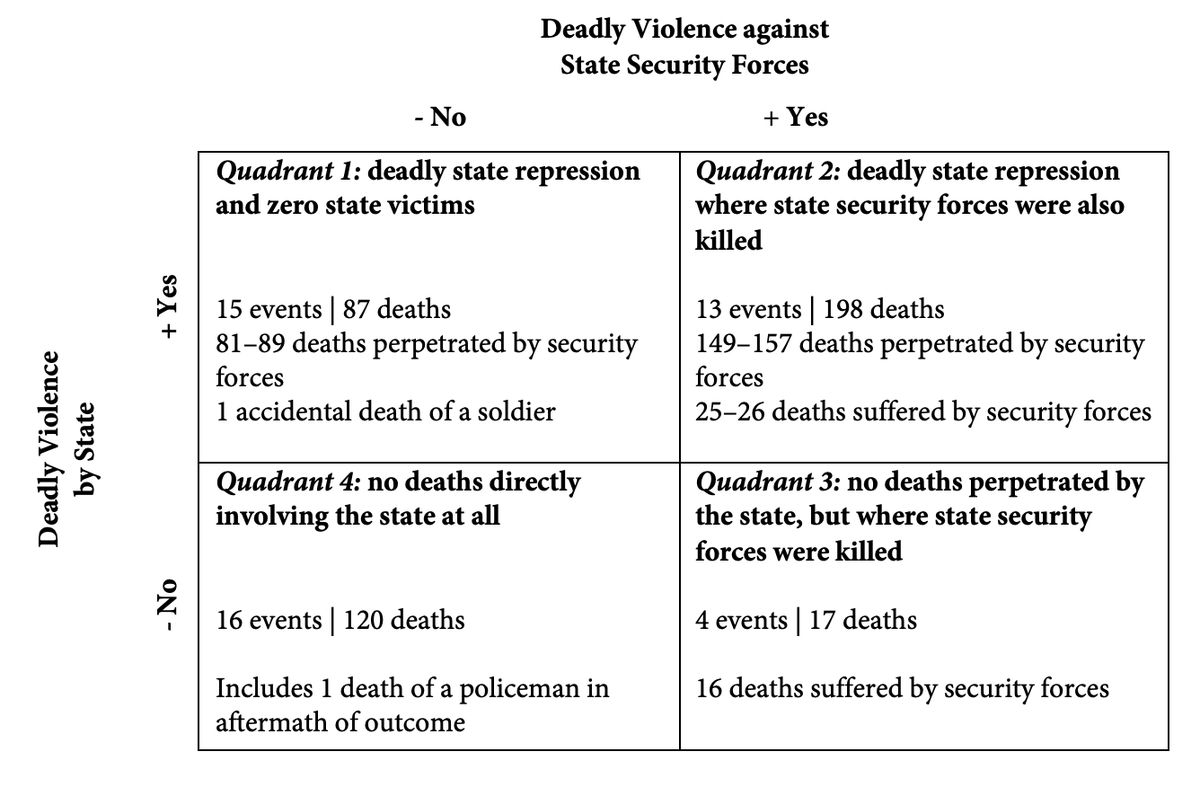

Resilience and mass, diverse participation seem crucial to Bolivian movement's success, but maintaining nonviolent discipline does not. How do I know? I divided the cases on this line…

-

Now, I knew going in that there were some successes in Quadrant 2, where there was deadly state repression but some security forces were also killed. Cases like the 2003 Gas War.

-

But I also knew of cases like the Cochabamba Water War in Quadrant 1, where movements won after absorbing unanswered deadly repression.

-

I thought this might be a good first use for the event-based data in Ultimate Consequences, which compiles around 600 deaths in Bolivia since 1982. my.vanderbilt.edu/cbjorkjames/2021/09/ultimate-consequences-project-overview/ As best I can tell, very few events are left out, so selection bias shouldn't be a factor.

-

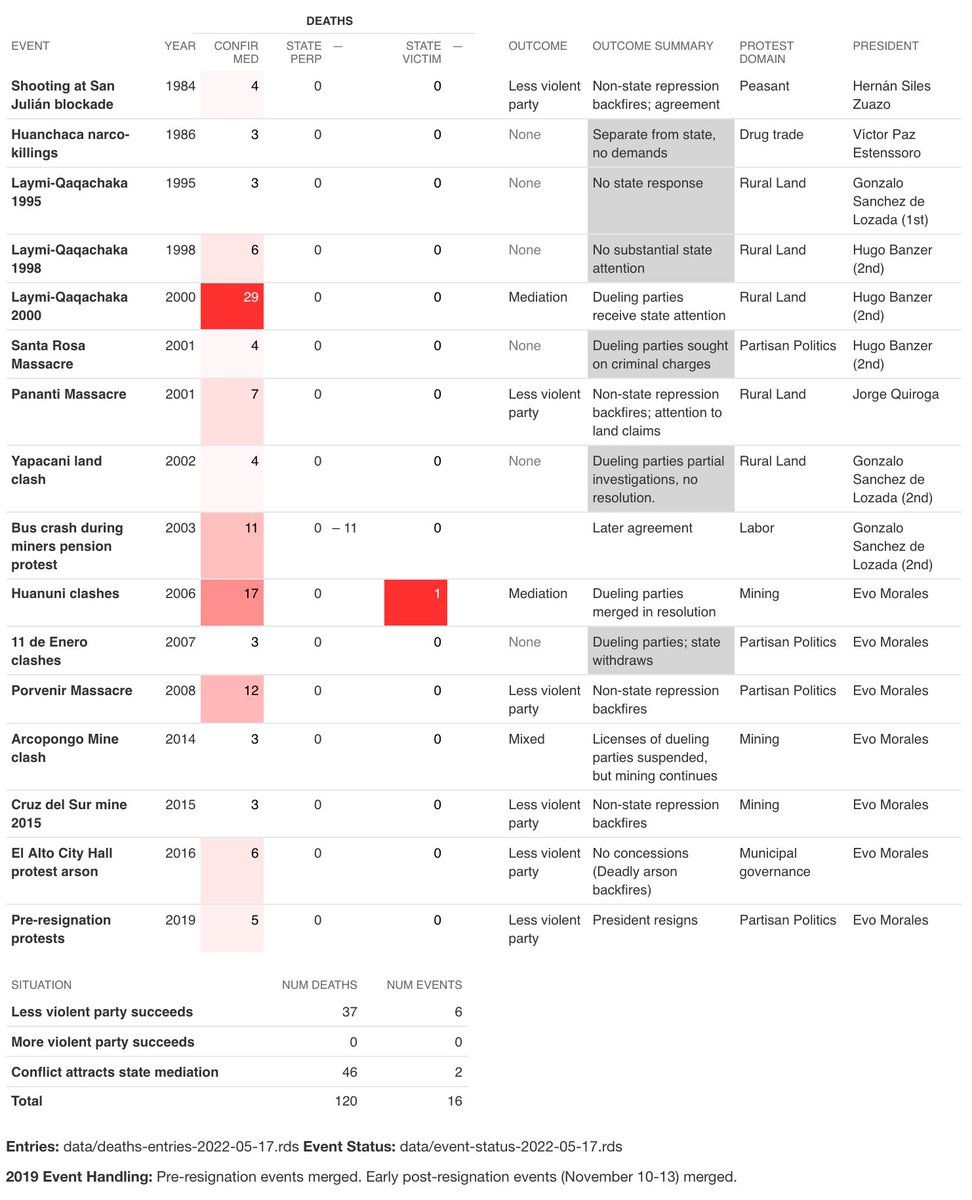

In cases where there was unanswered deadly repression, movements won 6 times, the state avoided concession 5 times, and there was one mixed outcome. In cases where security forces also suffered losses, movements won 7 times and the state avoided concessions 5 times.

-

You might notice that there are only 28 of the 48 cases in these two groups. Looking at cases without deadly state repression expands our picture…

-

This analysis is in an article currently resubmitted with revisions to Journal of Latin American Studies. Contact me for the current version or stay tuned for publication info.