-

@n_hold @Ethnography911 @GYamey Underlying peer-reviewed article (in which replacing more expensive retroviral therapies with cheaper STI treatments was an aside):

-

@n_hold @Ethnography911 @GYamey Oster, Emily. “Sexually Transmitted Infections, Sexual Behavior, and the HIV/AIDS Epidemic*.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 120, no. 2 (May 1, 2005): 467–515. doi.org/10.1093/qje/120.2.467.

-

@n_hold @Ethnography911 @GYamey Also interesting: Oster, Emily. “HIV and Sexual Behavior Change: Why Not Africa?” Journal of Health Economics 31, no. 1 (January 1, 2012): 35–49. doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2011.12.006.

-

@n_hold @Ethnography911 @GYamey In which Oster attempts to answer the question, why do Africans not change their sexual behavior when they get a positive HIV test? And concludes that it's a (neoclassical) economic response to shorter lifespans.

-

@n_hold @Ethnography911 @GYamey As with the 2005 article, the policy conclusion is spend more on other sources of mortality, such as malaria and childbirth, and people will change their behavior to avoid getting HIV.

-

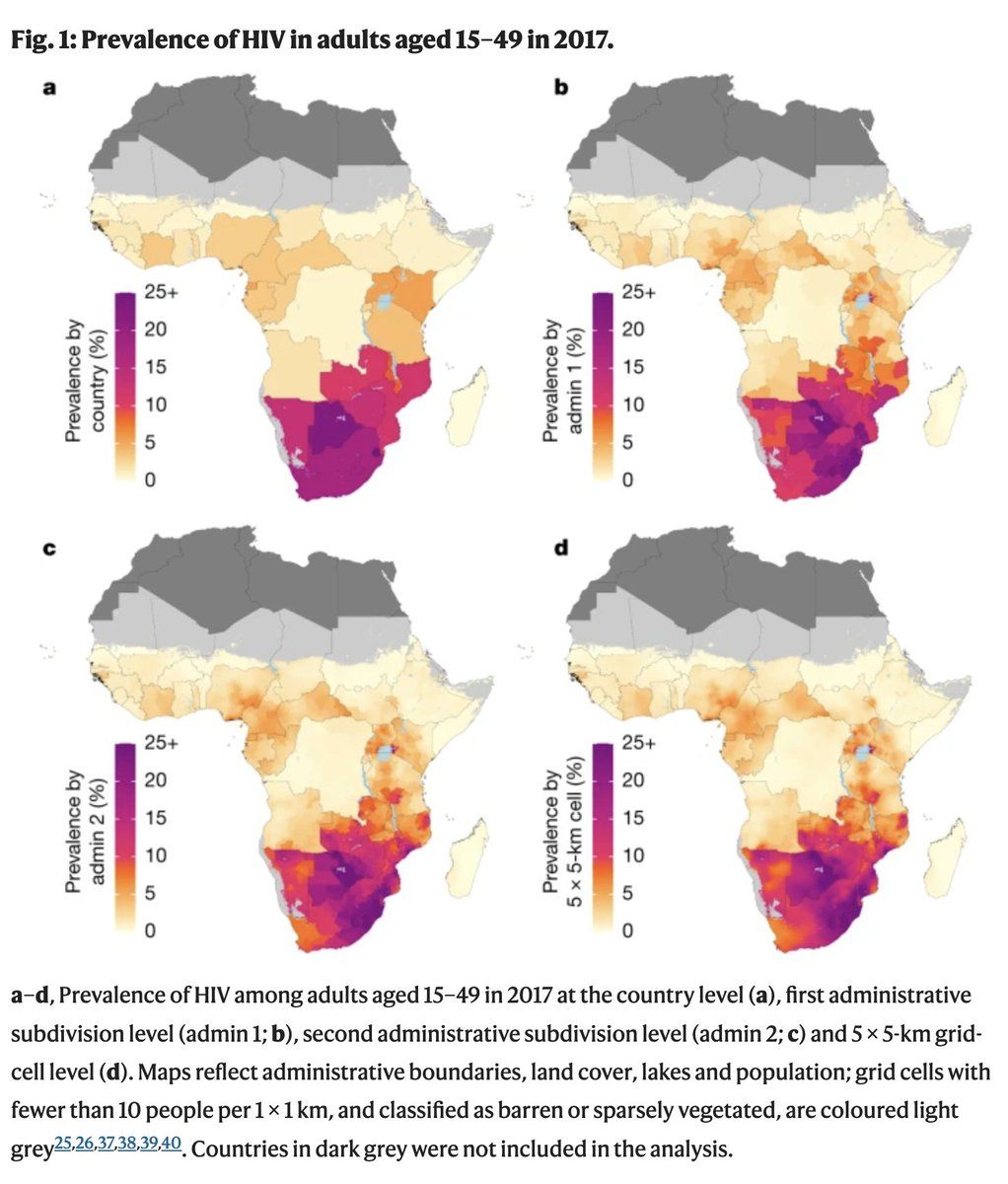

@n_hold @Ethnography911 @GYamey A relevant fact is that HIV prevalence in sub-Saharan Africa was very high, and that none of the millions of people who already had HIV could benefit from these hypothetical incentive changes.

-

@n_hold @Ethnography911 @GYamey 2017: "34% of people in east and southern Africa and 60% of people in west and central Africa who are living with HIV are not currently receiving any treatment"

-

@n_hold @Ethnography911 @GYamey Dwyer-Lindgren, Laura et al. “Mapping HIV Prevalence in Sub-Saharan Africa between 2000 and 2017.” Nature 570, no. 7760 (June 2019): 189–93. doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1200-9.

-

@n_hold @Ethnography911 @GYamey It's not literally incorrect to argue that it's cheaper to prevent malarial deaths than HIV deaths. But if one chooses to not spend money on the latter because the former is cheaper, they are consigning people to die of AIDS.