-

A recurring problem in Bolivia is one-eye-shut perspectives where (many external or pro-MAS) left observers only mention abuses by the right, and (many external or anti-MAS) right observers only mention abuses by the MAS. The solution is a more complete accounting. (thread) @jderpic/1377063613106642945

-

Mirror-image patterns of denial, a staple of social media spaces like this one and increasingly of the Bolivian mass media, do not imply symmetric patterns of violence and abuse. We have to investigate instead.

-

In the 2019 Bolivian crisis, property destruction began on October 21 with the burning of electoral offices, non-lethal police violence and inter-protester violence began later in October, and deadly acts began on October 29. First deadly state violence was after Evo's ouster.

-

Two important things how the Morales gov't handled the crisis… It essentially forbid the security forces from using lethal force. And it made prompt arrests in the cases of the three known deaths before November 10.

-

Looking more closely, the beating death of Julio Llanos was caused on October 29, but he was still hospitalized when Evo resigned. The gov't failed to find and prosecute the MAS supporters who beat him.

-

On the other hand, prosecutors charged and jailed a cluster of MAS politicians, activists, and associates for the shootings in Montero on October 30.

-

And it promptly arrested presumed perpetrators of the death of Limbert Guzman. These cases stalled somewhat under the Áñez government.

-

The death of Sebastián Moro, who was injured by an anti-MAS crowd the day before his fatal assault by unknown parties, was too late for the Morales government to investigate. woborders.blog/2020/04/17/sebastian-moro-death/

-

There was also potentially deadly violence: protesters in anti-MAS caravans from Potosí and Sucre (on the road to protest in La Paz) were taken captive and beaten on November 9, and attacked by sharpshooters on November 10, wounding at least six.

-

In parallel to that pro-MAS violence, anti-MAS partisans in Montero, Cochabamba and elsewhere assaulted opponents and burnt out buildings. During the police mutiny, this escalated further.

-

Despite a barrage of arrests of MAS activists, the Áñez government seems to have spent little effort on the deaths in Montero, Cochabamba, and La Paz, nor on finding the sharpshooters and kidnappers of November 9/10.

-

In summary (of the pre-ouster violence): The Morales government disavowed military force vs the anti-fraud movement or the police mutiny. It detained some pro-MAS violent actors, but pro-MAS violence shocked the country and contributed to the demand for Evo Morales to resign.

-

Anti-MAS arson and violence began on October 21, when it literally burned ballots, and continued through at least November 10, burning politicians' homes and party offices. But no one died til Sebastian Moro.

-

The above is a minor update from this analysis. After Evo's ouster, the violence got much worse, and responsibility shifted to the security forces and the interim government.

-

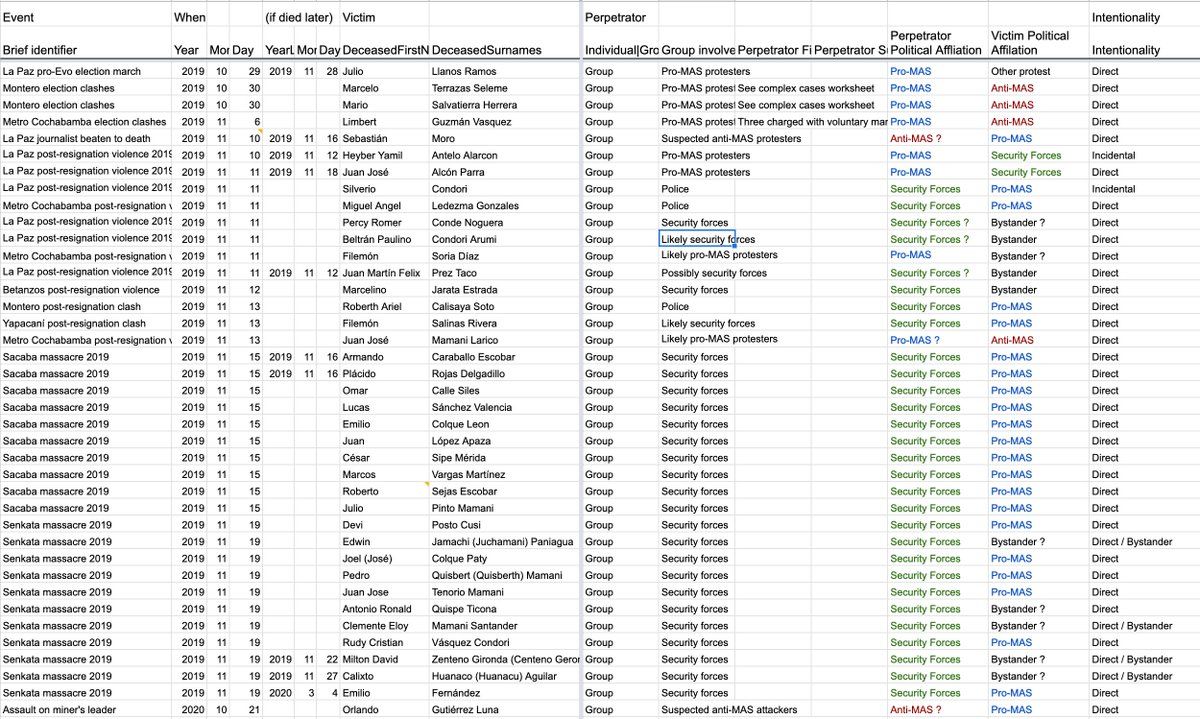

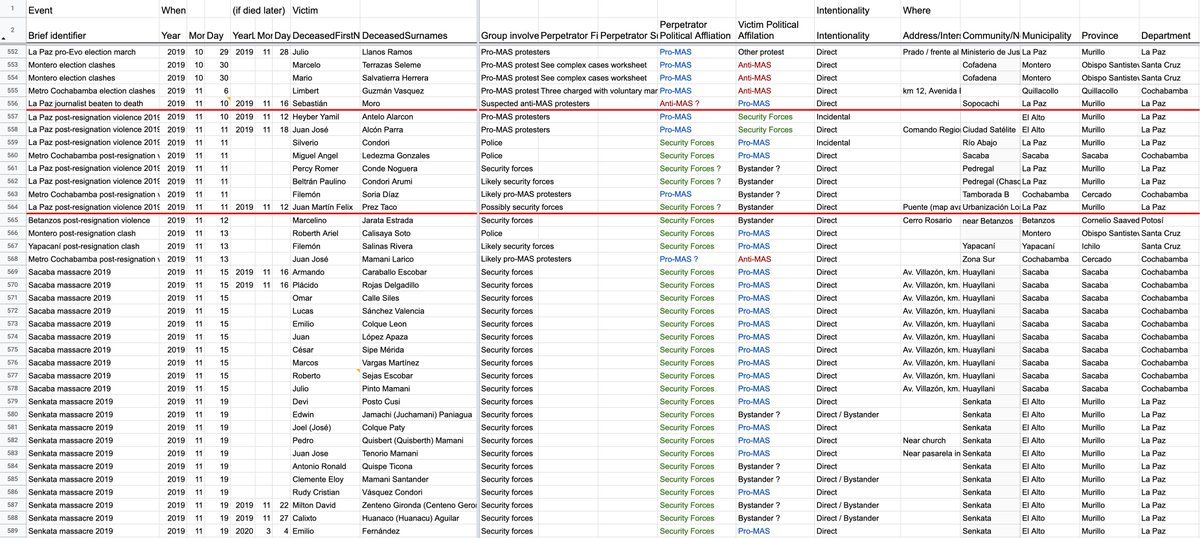

In January 2020, I wrote up a summary of all the deaths during the crisis here. woborders.blog/2020/01/04/2019-crisis-deaths-analysis/ A number of unknowns have been filled in since then, and two more died from wounds at Sacaba and Senkata, but it covers the sequence.

-

During the two-day military interregnum, there were two clusters of deaths. In El Alto, La Paz, and Cochabamba, pro-MAS demonstrators attacked police installations and looted. The security forces confronted them and other pro-MAS crowds.

-

In Cochabamba, two more were killed, as three-sided MAS / RJC / security forces clashes raged. This was a chaotic time, but a longstanding pattern of police/military overkill of unthreatening protesters and bystanders was already activated in La Paz.

-

Then, as the military executed orders to "pacify the country" they brought deadly force to scenes of confrontation in Betanzos, Montero, and Yapacaní, killing one in each place on November 12–13.

-

By Bolivian standards, this a lot of deadly state force: 5 to 8 killings in three days. It looks like the predictable result of using the military for crowd control, something that was restricted in 2004.

-

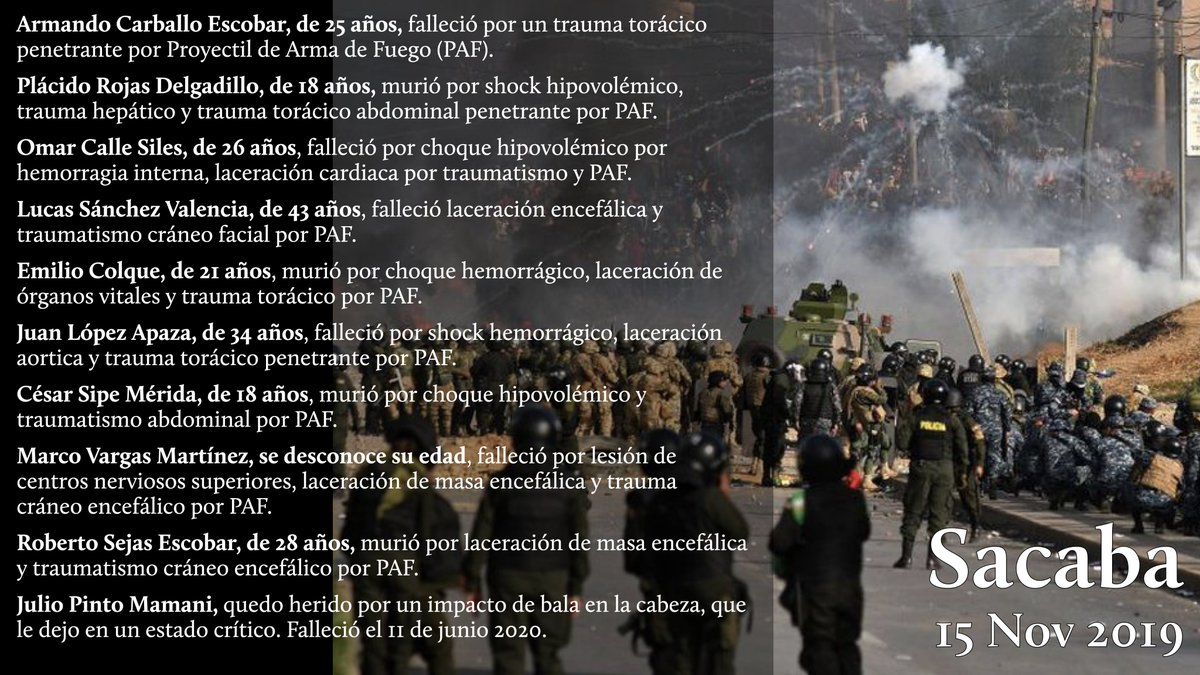

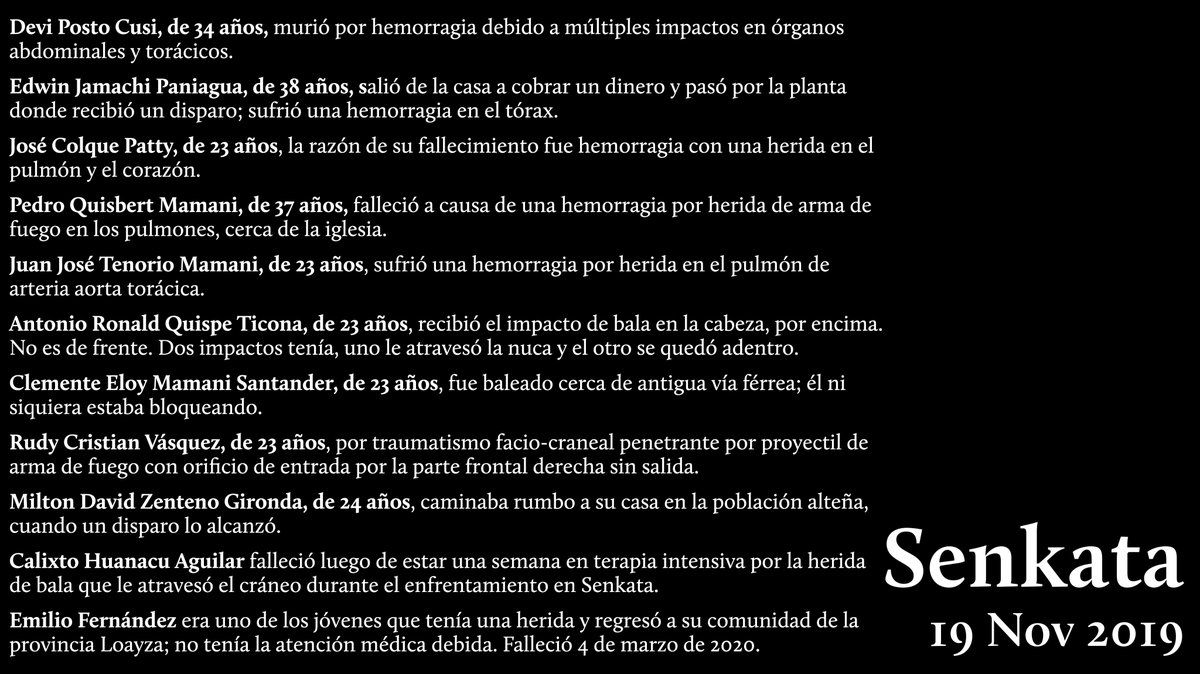

Part three of the crisis begins with the Áñez presidency (Nov 12) and her decree authorizing national "pacification" through deadly force on November 15. This would be deadlier than the rest.

-

In the aftermath of the Sacaba and Senkata massacres, there have been ludicrous allegations that the protesters "shot one another" or were engaged in "terrorist" acts justifying their deaths.

-

In fact, negotiated de-escalations of protests occurred in the hours prior to each massacre. Abundant evidence of military firing was always there. And there was never a substantive risk of a gas explosion at Senkata.

-

Still shocking to me is the right-wing narrative that these events were essentially MAS-orchestrated massacres, regardless of who fired the shots. @edamsoft/1377322549873238017